How to end factory farming

Theories of change through a startup lens

Factory farming is really bad. It’s by far the greatest known evil that society opts into. We could choose to arrange our society in a way where we don’t consume animal products, but we don’t: we actively demand meat, eggs, milk and leather. The demand for these products is fulfilled by production processes which house animals in tiny cages, separate calves from their mothers, slaughter them inhumanely and all the other awfulness that I don’t need to list because you’ve certainly heard it before.

The horror is so grotesque that it seems obvious that our future society won’t be torturing animals. How can we most effectively work towards getting to that future faster?

I’m a tech entrepreneur with expertise in consumer products—I founded Wave1 which builds financial services in Africa, scaling to millions of users and thousands of employees. I’m now interested in using my skills to make progress against factory farming, and have been researching and talking to animal activists, entrepreneurs and funders in the US and UK for the last few months. In this post I’ll overview a wide selection of potential approaches using a startup lens: We want ideas that can grow quickly, show traction and have potential to scale up, ultimately ending factory farming if they succeed. I’m looking for early, concrete and measurable signs of success.

For this post, I’m focusing on the US and UK2, and on ideas that have the potential to end factory farming3. I’ve linked a lot of interesting projects in the footnotes.

Individual moral choices

Perhaps individuals might wake up to the badness of factory farming and decide not to participate in this system. If we get the message out there enough, then most people will collectively choose stop demanding factory farmed goods, and this will effectively end the practice. The industry will be reduced to a tiny fraction of what it once was.

This has been a longtime approach through various iterations of the “go vegan” message since at least PETA in the 1980s, the UK Vegan Society in 1944 and so on. It has not made much progress; the number of vegans in the US/UK has been stable for decades4.

This is a sad trend. The message is not resulting in behavior change despite broad awareness5.

Compare to emotional/psychological abuse of a partner, which is in most cases legal, but considered wrong, socially unacceptable and a reason to shun the perpetrator. Most people recognize wrongness of factory farming at some level and yet eating meat is still not only acceptable but often socially encouraged—certainly people aren’t shunned for it.

One big difference I can see is that there’s an industry to blame. When you abuse someone there’s no third party involved, but when you buy your groceries you can punt at least part of the problem to the suppliers and that might reduce your perceived obligation to change your own behavior.

Another difference is visibility contributing to normalization: consuming animal products is a publicly visible everyday thing people do. We see people doing it and that reinforces its normality—even if we privately think it is wrong, it’s very hard to call it out or become convinced to stop.

My take: while I’m deeply grateful for vegan advocacy since going vegan was great for me, there is very little traction on advocating for the broader public to go vegan and so I don’t see this path as particularly promising to work on right now. Changing my mind on this would take seeing veganism growing very fast in some pocket of mainstream society, not just activists.

Reducing meat

What about convincing people to reduce their consumption of animal products, even if they won’t make a big switch all at once? Perhaps people are unwilling to declare a new identity (especially one with so much baggage), but they might be convinced to make occasional pro-animal decisions like shifting some calories away from meat. And over time, small shifts can sum up to a big change in the prevailing norms.

It’s hard to know how quickly this idea can work. Certainly I know quite a few people who have actively reduced meat through some combination of ethical, environment and health reasons. The Veganuary campaign encourages people to try going vegan for January and has gained substantial traction and celebrity endorsements across the world; Meatless Mondays is a similar campaign.

Unfortunately if the reduction message were working at scale, we would see per-capita meat consumption declining in the US or UK, and we don’t yet see that6: it’s stable. It’s mildly encouraging that it peaked in 2004-2006 after decades of slow growth, so maybe something is working but it’s super unclear from the top line numbers.

To get a more leading indicator of traction we might try to get a measure for how many “meatless meals” people are eating and whether that number is going up. I did a few Google Trends searches for things like “chicken substitute” but it’s hard to come to strong conclusions (it does appear that demand for chicken substitutes peaks in January—perhaps due to Veganuary?—but similar-seeming queries produce differently-shaped results, and the trend is not particularly upwards since 2020). Great traction would look more like an exponentially growing curve: doubling every year, or something, and none of the charts I found look like that. One exception is a piece by Chris Bryant in 20247, where he cites several charts that seem to demonstrate traction in the way I am hoping for, but (e.g.) the Google Trends chart he references peaks in 2020 and declines after that, and I wasn’t able to find strong data supporting continued growth since the early 2020s.

My take: the main argument for meat reduction programs is that they have shown that they can grow quickly via influencers to large portions of the population who care about animals but not enough to adopt a vegan diet. The main argument against is that the recent traction is not strong, and it is hard to imagine a viral/exponential growth pattern. Overall I’m cautiously optimistic about the idea space but want to see more efforts on community-based growth strategies that can scale beyond influencers.

Improving industrial conditions

Factory farms have gotten worse in many ways over the last few decades. First, as costs have fallen and demand has increased, we’re putting a lot more animals through these awful conditions. The number of chickens farmed worldwide has roughly doubled since 20008 and nearly all of that growth is factory farming conditions. We’ve invented and popularized new ways to cage animals more densely (e.g. gestation crates were popularized in the 1990s9).

Factory farms have also gotten better though: in the US, we’ve gone from 4% cage-free housing for egg-producing hens in 2010 to 40%+ in 202510. Other bad practices seem to be on the decline (e.g. gestation crates for pigs and male chick culling).

Retailer Campaigns

The last decade of positive results have mostly come through corporate campaigns: putting public-relations pressure on companies who have an incentive to keep a positive consumer image, usually retailers—restaurants and grocery stores. They view sourcing higher-welfare eggs as an easy change they can make for low cost to improve their public image. Similar campaigns are working on advocating for better conditions for farmed pigs.

While this strategy has both momentum and is actively and measurably improving things for animals, I think the impact is limited since we are probably picking up low-hanging fruit. I expect this strategy to trail off—for example, McDonald’s will probably never stop selling eggs entirely through pressure campaigns, nor will they ever source eggs from small high-welfare farms, but increasing pressure can give them strong incentives to welfare-wash their eggs in increasingly byzantine ways. More generally, companies will not take actions which risk the success of their product lines, and I also expect them to develop “antibodies”—brands and strategies which are more robust to pressure campaigns. Finally, public attention is limited and it might be hard to continue drawing attention to bad practices over time.

Could successful campaigns cascade? Some early forms of cascading are already happening: early successes serve to demonstrate that a pressure campaign worked on one company, so they can move onto competitors with more social proof as ammo. But I’m much more worried about whether cascades can sustain all the way through to social change, since companies are rarely compelling advocates for anything unless it affects their bottom line, but that would require a broad stigma against animal abuse and I don’t see it happening without a broader upstream societal change.

My take: Keep doing campaigns while it’s cheap and working, but redirect effort if it loses efficacy/traction.

Tech improvements

I haven’t yet mentioned technology improvements but this is a huge factor with a ton of potential to improve things quickly. Chick culling is on the decline because there’s technology to check the sex of eggs before the chicks hatch. Such tech gets adopted quickly because it improves the efficiency of farming, but you can imagine that it’s worth differentially investing in technology that improves welfare while also helping factory farms. For example, you can imagine automatically monitoring livestock using AI to identify chickens or pigs in distress, or creating higher-welfare chicken breeds which grow as fast as the existing breeds.

Unfortunately I don’t feel excited or optimistic about working on most tech improvements for three reasons. First, more mechanization and automation has not historically been good for animals; we have to think that we’re especially smart and careful to produce only good forms of automation. Second, helping factory farms adopt tech we build is a form of symmetric capacity-building—they’ll have an easier time adopting all tech, not just the tech that we think is good for animals, and they’ll make more money, giving them more capacity to entrench. And above all, the deep moral issue is that our society exploits animals in the first place; better tech seems in most cases to make the conceptual moral issue worse.

My take: Don’t think I want to spend much effort on tech improvements that seem like they might help factory farms make more money or operate better. While such ideas are often promising for short-term suffering reduction, most are double-edged, and I’d rather focus efforts on societal change. What would change my mind: maybe seeing more examples of tech improvements that have made an entrenched industry weaker rather than stronger.

Competing in the market

Can we produce non-animal products that successfully out-compete animal products? There have been many attempts. Beyond and Impossible meats were darlings of the 2010s boom in alt-proteins, and even before I was vegan I adopted them into my diet and ate them on a weekly basis. We have a tremendous variety of great products now, too many to list.

Ethical Substitutes

Maybe we can make meat alternatives that are roughly competitive in price, health and taste, and the ethical arguments against animal exploitation will convince people to switch? Beyond and Impossible are great examples of this. They’re cheap (but not as cheap as beef), they’re probably a bit healthier than beef, and they taste pretty good. The theory goes that people will adopt the products for health, environment or ethical reasons, and over time it can slowly become the default. Unfortunately, this plan hasn’t worked out yet and it’s not exactly clear what’s blocking the progress11.

Maybe substitutes are good but not good enough yet? Impossible meat is tasty, but not ultra-satisfying when you want a beef burger; same for eggs. If it were like conventional vs. free-range eggs where the product is a perfect substitute then people would switch, but the bar for producing plant-based perfect substitutes is insanely high and we aren’t remotely close technically. Many people are very sensitive and discriminating when it comes to their food and producers never want to make their product noticeably worse, so the only route to victory is if everyone agrees that the plant-based substitutes are perfect. This is a very difficult condition to achieve on a pure technical level, and then we have the additional baggage of decades of awful-tasting substitutes (e.g. frozen veggie burgers) which pushes against omnivores accepting new substitutes even if they’re quite good.

Worse, I am still fearful that even perfect substitutes won’t work because there’s a ton of cultural identity momentum around eating animals. It’s very hard for me to imagine convincing my family to roast a plant-based turkey for Thanksgiving, even if the turkey tasted identical, because everyone is excited about the ritual of preparing an animal for a fancy dinner and we’d be giving up on a whole bunch of traditional nostalgia around the practice we’ve built for generations. The same might be true on a smaller scale for something as simple as a takeaway chicken burrito, where you just want the same thing you’ve had every week for years, because you have tons of positive associations with it and any change seems scary and not worth it. Even if there are perfect substitutes (e.g. experienced tasters cannot tell the difference in blind experiments), meat advocates will seed fears and doubts about the substitutes for all kinds of reasons, will strenuously object to being served it and these efforts will likely slow the adoption of the substitute.

My take: Current adoption rates are mediocre for ethical substitutes, and I’m quite disappointed about this because there are incredible products in the market and it’s still not working. I think we should probably not rely on this path, sadly, despite my great personal joy in having such a variety of products available. What would change my mind is seeing more restaurants adopt Beyond or Impossible as a default hamburger rather than a vegetarian alternative.

Pure Competition

Maybe pro-animal entrepreneurs can succeed in pure market-based competition, i.e., make something better than animal products that people want? Soylent and Huel are good examples of vegan meal replacements which appeal to non-vegans because they’re more convenient and healthier. They don’t appeal to everyone though.

My take: I think we can slowly popularize new proteins and new dishes, building up cultural momentum for new types of foods. But it’s slow and doesn’t rely much on recognition of the badness of factory farming. I think we can find faster, more direct paths. What would change my mind is seeing fast adoption of novel foods that are tasty, that make use of a vegan message to grow faster among the mainstream.

Institutional foodservice choices

If individuals struggle with moral conviction on their own—especially if they need to stand apart from their groups to make more ethical choices—maybe we can convince groups to make better moral choices all at once for the food they eat together. For example, a school might decide to make plant-based meals the default first option. I expect two effects from this: first, people directly change their behavior when faced with new defaults12; but second, it normalizes plant-based eating and makes it easier to advocate for change elsewhere.

We should start by targeting institutions and groups who are most susceptible to rapid change: probably those groups which are already heavily populated by pro-animal advocates, or institutions where advocates can make powerful arguments for more inclusive or accessible food service.

A simple example is conference food. Effective Altruism conferences serve food to a wide variety of people but with a high percentage of vegans (about 25% in the EA community13); the organizers were convinced to default all food to vegan at these conferences, with very limited exceptions. Conferences might be a small portion of overall food service, but offering excellent plant-based food at conferences is a good way to show off what’s possible to a captive (and potentially influential) audience.

Primary and secondary schools seem like another promising path for early wins. In general, schools are obliged to serve food compatible with many types of dietary restrictions, and it’s easy to argue that plant-based defaults are one of the best and easiest ways to satisfy a wide variety of dietary needs—after all, vegan food is also vegetarian, halal and kosher by default. I think it also helps that the parents aren’t the ones eating the food (the kids are), and so those parents who prefer eating meat have less incentive to argue for the status quo.

I’m also excited about the upstream nature of schools and universities in particular. Students who graduate will take their norms with them to the rest of society.

My take: I’m optimistic about institution-level foodservice advocacy if it can become self-propagating over time. Maybe the first few schools change through hard work by activists, but hopefully the norm cascades and eventually institutions will see the necessity of changing to stay competitive. Let’s follow this path as long as it seems promising, pick up the easy wins first, try lots of different institution types and look for cascades. If we don’t see at least some local cascades after a while then it’s probably not working.

Newsmaking, Policy & Legal

OK so what’s the endgame?

We must, and we will, end factory farming in society eventually. The question is how to get there the fastest. In general, societal changes follow public opinion, but it’s a bit hard to know what public opinion actually is on this issue—public surveys show that people are broadly and strongly against factory farming, but this has not yet led to change. Attempts to pass popular laws against factory farming have invited concentrated, usually successful opposition from the industry.14

The book Engines of Liberty by David Cole (written in 2016) gives an example of political change that happened quickly but with many fits and starts: same-sex marriage. To take a single US state: in Hawaii in 1991, a court denied a same-sex marriage license. Escalating this led to a 1993 decision where same-sex marriage was declared legal by the Hawaii supreme court. This of course triggered more backlash and national discussion of the issue. As a result, in 1998, Hawaii passed a constitutional amendment and legislation banning same-sex marriage. Discussion continued and public opinion changed over the next 15 years such that by 2013 the public reversed the legislation and legalized same-sex marriage statewide, and finally in 2015 the US Supreme Court guaranteed the right to marry to same-sex couples across the US.

We should expect that the eventual ban of animal farming will have similar ups and downs at each stage. The theory is something like, if you make powerful moral and legal arguments and pick the right battles, you can win change very quickly through policy advocacy; sometimes backlash is helpful because it keeps the discussion in the news and brings out supporters.

The theory seems to depend on the issue being in the news, triggering discussion. So one key bottleneck seems to be whether advocates manage to get and keep factory farming in the public discussion—repeating the same messages about factory farming that have been true for decades isn’t the best way to stay relevant.

To learn more about this broad strategy, I recommend This Is An Uprising by Mark and Paul Engler. There’s a lot in there about different ways to change the world through activism—here’s one example of creative newsworthy activism from Otpor, a successful resistance movement against Milosevic in Serbia:

In another now-famous prank in Belgrade, a troupe of activists placed a steel barrel emblazoned with Milosevic’s image on a busy walkway in one of the city’s central pedestrian shopping centers. Next to it, they placed a baseball bat. Signs invited onlookers to either drop a coin into the barrel “for Milosevic’s retirement fund” or—if they did not have a coin “because of Milosevic’s economic policies”—to take a whack at the barrel. Within 15 minutes, a large crowd had formed of shoppers eager to take turns at bat. Police soon arrived on the scene. But finding no evidence of the activists who set the stage, they were not sure whom they should arrest. Eventually, they took the barrel itself into custody, much to the delight of the independent media. (This Is An Uprising, ch.3, p.85)

Applying this to factory farming takes some creativity. Rescuing animals from slaughterhouses and farms15 seems promising as a way to trigger discussion of the conditions (via high profile sympathetic court cases), but there are clearly other avenues, like lawsuits and planning objections16, ballot initiatives17 and disrupting events that highlight animal cruelty18. I also wonder whether it might help to highlight negative experiences of humans working in the animal agriculture industry—this tactic apparently helped the abolition of slavery in the UK19. Or anything else, such as campaigns around offsetting the harms of meat-eating20, that can create discussion. Regardless, a scattershot approach seems wise since news is very hits-driven.

My take: I’m quite optimistic about policy and legal angles starting with newsmaking and attention-gathering as the obvious first step. Any attention can be used as a platform to make powerful arguments to the public, which can help with policymaking and court decisions, which can make it easier to push for more changes and thus cascade into further newsmaking. To me, this is the strongest potential feedback loop I’ve seen, but it’s hard to know where I can make a difference since a lot is already happening. I’ll be seeking ways to get news primarily, but also ways to convert that news into actions that are working for the mainstream.

Inside Lobbying

There might be an angle for ending factory farming via inside lobbying—strategies based on connections and money, that don’t require much activism, newsmaking or having factory farming be discussed publicly much more than it already is. We know the industry we’re fighting relies heavily on private lobbying and this has a massive effect on the law, e.g., they consistently manage to pass and increase US animal agricultural subsidies21.

In 2023, the US Supreme Court upheld the power of states to set animal welfare standards for products sold there, which was a huge blow to the industry. Since then they have made several (so far failed but still up-in-the-air) attempts to reverse this progress through Congressional acts22 which have garnered a small amount of public attention. I’m not quite sure how to interpret this—does it mean that inside lobbying isn’t as powerful as it seems? Perhaps the small amount of attention spooked legislators? Or does it mean that inside lobbying has the power to set the agenda even if not always win, and is thus worth investing more? I’m uncertain, but lean towards it being worth working on.

Could this actually achieve our goal? I think yes: over time, incremental legal changes can slowly end factory farming—imagine laws are passed which raise costs for larger farms (perhaps starting with labeling requirements and environmental impact mitigation), making it harder to start and operate big factory farms, and ratcheting up requirements over time. This will certainly pass through to consumer prices rising over time and maybe better consumer awareness. If we also manage to ban low-welfare imports and support high welfare pasture farming and plant protein innovation, then I can imagine that factory farming could eventually be totally uncompetitive and that would end it in practice.

How is inside lobbying actually done? Essentially, you meet with politicians, who will meet you because you offer money or influence. The money part you can raise from private donors (unrestricted political donations are capped per person at a few thousand dollars per campaign, so it really helps if you can get lots of semi-wealthy people). For the influence part it seems like the straightforward way is to build a base of a lot of people who legibly might change their vote in primaries based on your recommendation. The National Rifle Association is a good example of a large, politically-powerful nonprofit built around a single issue. They are effective at mobilizing their members to vote a certain way based on this issue23, and this gives them a ton of power in the US. There are probably other influence-based strategies that are more based on connections rather than voting but I don’t yet have a good handle on it.

My take: This is a big question mark for me. I don’t yet have good models of how government works, but I think it’s worth trying to do more on the inside lobbying angle, especially building a voting bloc, to see how much traction we can get. I’ll be seeking ways to make being part of the bloc appealing.

Upstream in the supply chain

Before we close, let’s take a look a bit further upstream.

For poultry and pigs, the big players like Tyson are called “integrators” and they breed the animals to produce chicks and piglets. The animals are owned by the integrator at all stages, but housed in & raised by individual farming businesses—“contract farmers”—who are heavily dependent on the integrators. The integrators eventually reclaim the animals for transfer to the next stage or slaughter at their own facilities.

For cattle, both beef and dairy farms breed and calve their own animals. In beef, independent ranchers sell weaned calves to feedlots, which fatten them before selling to slaughterhouses. In dairy, the farms sell the milk daily through a cooperative or directly to a processor.

In all cases, from the slaughterhouse onwards there’s a highly concentrated meat supply chain owned and operated by a small set of companies (Tyson, Cargill, etc). They slaughter, butcher, pack, refrigerate and distribute to grocery stores and as such they have tremendous industry power.

It seems that the big integrators have a stranglehold on the whole production process, but maybe contract farmers are a weakness since many of them are basically being exploited by the integrators and seem not to be super happy with the contracts they’ve signed. It made me check whether there are programs to help contract farmers get out of their poultry or pig-farming contracts, and indeed there are24, although it’s hard to tell if such programs can grow fast since everything is so early, and I also don’t quite know what the endgame is (although probably anything we can do to disrupt the industry is good and will result in higher costs, which can cascade into a win).

My take: The contract farmers might be a vulnerability for poultry and pigs—if they are indeed being exploited by the industry, and they know this and we can reach them and offer them compelling alternatives, I think there’s potential to make a big impact. I’ll be looking for early product-market fit for these programs—hopefully it becomes clear that farmers are already seeking some change, and that the program can offer a real solution.

Wrapping up

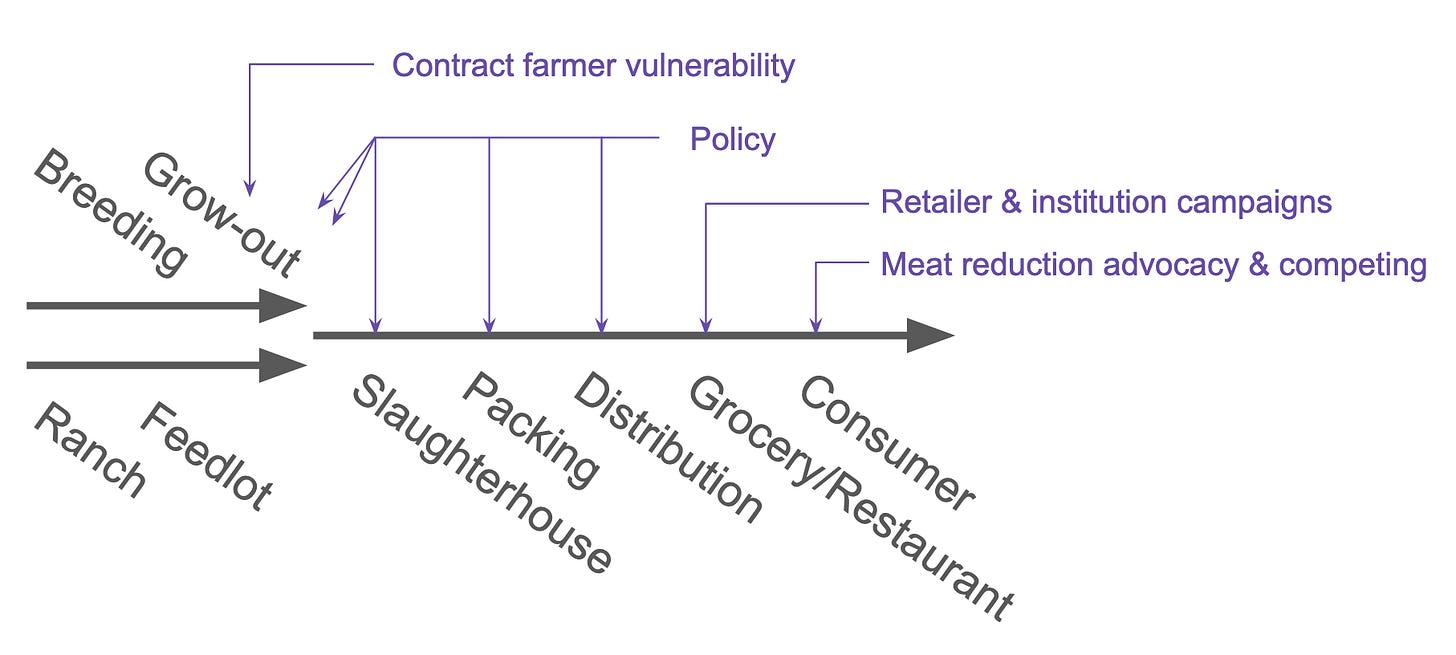

I made a diagram of where the proposed interventions operate:

Through the process of drawing this up, two things became apparent that I’ll highlight.

First, a huge portion of all these theories of change funnel through consumer demand in some form. Originally I thought consumer demand was only referring to what people actually choose to buy in the grocery store, but the map made me realize the demand actually cashes out in tons of other ways: which restaurants people go to, which grocery stores they shop at, where they send their kids to school, what conferences they attend, which politicians they elect and what policies they support. This makes me upweight ideas that involve convincing the public that we have a problem, even without making a specific ask.

Second, that I hadn’t really deeply considered where else in the upstream supply chain is vulnerable. The map-making process caused me to add the contract farmer vulnerability, but there’s a lot of interesting steps along the line; do you see anything else promising?

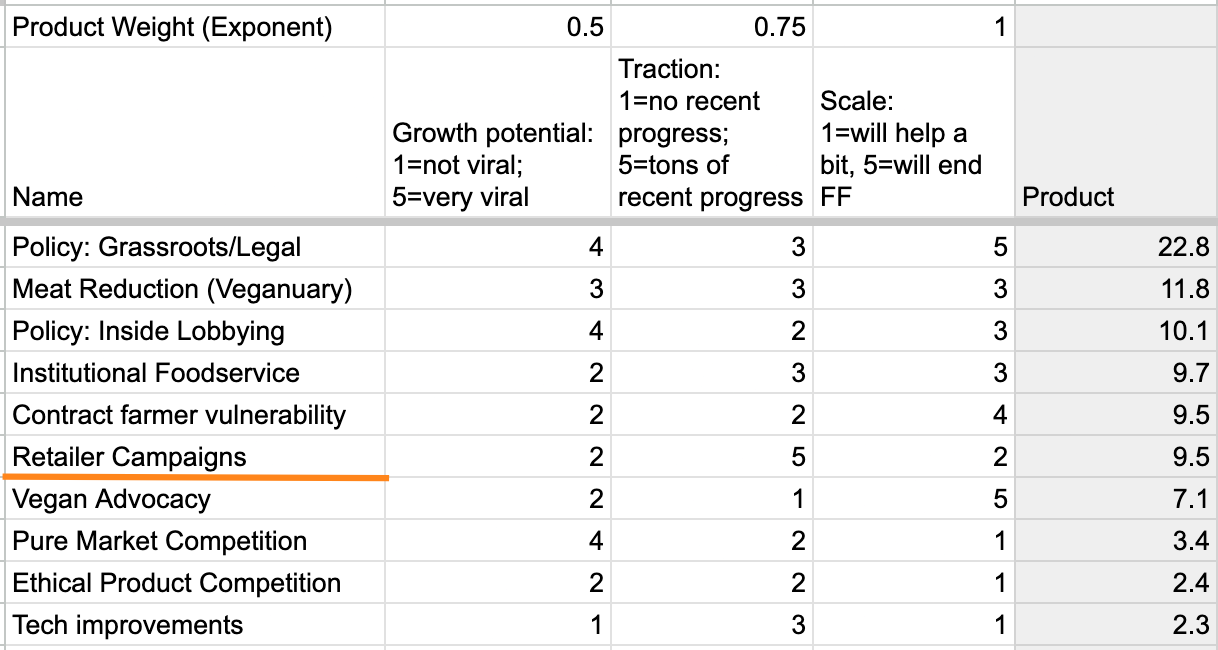

Let’s make a weighted factor model

My criteria are: can grow quickly, shows traction, and has potential to scale to ending factory farming. I’m going to combine these three factors using products rather than sums since my instinct is that they work like bottlenecks.

It’s very rough. You’re welcome to duplicate and mess with the scores and weights, if you want; I’ve bumped around until it roughly matched my intuitions, although Meat Reduction ended up higher than I expected. I think everything above and including “Retailer Campaigns” is above threshold for working on.

Ultimately this is an ecosystem

Many of these efforts boost each other. Any amount of newsmaking is helpful for everything else; new vegans might follow a ladder of engagement and get more involved (like me!); campaigns and lobbying can sometimes result in news; and overall movement momentum matters. So unlike a startup, where the best strategy is usually to put your head down and focus, movement-building benefits from quite a bit of awareness and cooperation with other folks who are doing similar things. This means it’s a bit less important to pick the best strategy.

If you are working on something against factory farming where there’s good traction, even if it’s not one of the top areas I highlighted above, I’m very interested in hearing what it is. Please share any other thoughts too!

I was a cofounder of both Wave and Sendwave. Wave is focused on phone-based financial infrastructure (mobile money) in West Africa; it competes with other mobile money services like MTN MoMo and Orange Money. Sendwave was acquired by Zepz and is focused on international transfers (remittances) and competes with e.g. Western Union and Remitly. These companies have raised money from Y Combinator, Sequoia Heritage and Founders Fund among others.

Why? This work is fundamentally a cultural project; I think someone could redo the analysis for different cultures but I’m American and not native to any other culture. Even the UK is a bit foreign to me, but I’ve spent enough time with animal people in the UK that I feel I have a solid picture for what’s being worked-on here, so I decided to include it.

I’m not prioritizing animal suffering reduction: although such work is certainly heroic and worth many people’s effort to work on, my moral instincts and interests point me towards projects that could end factory farming outright.

US—Gallup since 1999: https://news.gallup.com/poll/510038/identify-vegetarian-vegan.aspx; UK—YouGov since 2019: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/society/trackers/dietery-choices-of-brits-eg-vegeterian-flexitarian-meat-eater-etc

ASPCA—79% concerned about animal welfare on factory farms: https://www.aspca.org/sites/default/files/2023_industrial_ag_survey_results_report_052523_1.pdf

Chris Bryant in The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/veganuarys-impact-has-been-huge-here-are-the-stats-to-prove-it-221062. For the Trends chart in his article, I emailed Chris for his methodology and he specified that he was searching the “veganism” topic. https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&geo=GB&q=%2Fm%2F07_hy&hl=en

World Animal Protection: https://www.worldanimalprotection.us/latest/blogs/gestation-crates/

The Unjournal has announced that they are currently doing an investigation on this: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/3Eh8MbqLwFBsD7GK2/how-much-do-plant-based-products-substitute-for-animal

Better Food Foundation advocates for this strategy: https://www.betterfoodfoundation.org/research-and-reports/research-plant-based-defaults-work/

See the “Diet” section of the demographics: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/z4Wxd2dnTqDmFZrej/ea-survey-2024-demographics

For one recent example, a 2024 attempt to ban slaughterhouses in Denver was strongly opposed by animal ag industry and lost badly at the polls: https://www.agpros.com/articles-and-information/denver-io-309-will-ban-meat-processing

This is called “open rescue” when it’s done primarily for the purpose of newsmaking. Direct Action Everywhere in the US and Animal Rising in the UK are activist organizations who have done a lot of this in recent decades.

Legal Impact for Chickens sues perpetrators of animal cruelty in the US: https://www.legalimpactforchickens.org/. Coalition Against Factory Farming mobilizes local residents to block new factory farming applications near those residents’ homes: https://www.caff.org.uk/caff-campaigns

Pro-Animal Futures does ballot initiatives in the US: https://proanimal.org/campaign-announcement-part-1/

Animal Rising has done some high profile disruptions of horse and dog racing events in the UK: https://www.animalrising.org/trials

“Clarkson knew he needed other arguments against the slave trade, so he turned his attention to the fate of British sailors on slave ships. That’s right, one of the greatest abolitionists of all time shifted his focus to the suffering among the perpetrators.”

—Moral Ambition by Rutger Bregman

FarmKind makes a meat-eating offset calculator which has successfully triggered a lot of discussion and debate: https://www.farmkind.giving/compassion-calculator

American Enterprise Institute explains some of the subsidies: https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/big-but-not-beautiful-agricultural-policy-in-the-2025-budget-reconciliation-bill/

The EATS Act, now called the FSFP Act, would reverse a recent Supreme Court decision upholding the power of states to set welfare standards for products sold in their states (e.g. California’s Prop 12). https://www.farmsanctuary.org/news-stories/act-now-safeguard-farm-animal-protection-laws/

This strategy is laid out in the book Get Political For Animals And Win The Laws They Need.

The best article I found summarizing the opportunity is on Foodprint: https://foodprint.org/blog/contract-livestock-farmers

Mercy for Animals’ Transfarmation program seems to be the main US example but there are others, such as SRAP’s Contract Grower Transition Program.

All such programs are very early, with low but nonzero traction.

I disagree a bit with a few of the weighted values but the one that stands out to me is a 1 out of 5 for pure market competition in terms of scale.

When looking back at other areas where animal products have been decimated, going from 90%+ of the market to less than 10%, it's generally been because of innovation and market competition. You can see this with the fur industry since the 1800's, whaling, and horses being used for transport/manufacturing.

There is room for more approaches now but I'd be surprised if this wasn't a key factor in ending factory farming.

thanks for this extensive piece.

I can't help but think that today we should give special attention to interventions that can help lower resistance or backlash - so many of the interventions you list might work better. Not exactly sure how to do that though :)